Calvin, Piety, and the Heart of Ministry

(Part 1)

[Editor’s Note: This is Part 1 of a two-part survey of Calvin’s understanding of pietas for ministry today. For Part 2, click here.]

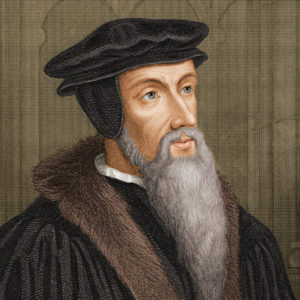

John Calvin, a man exiled and marked for death, lived a life of extreme challenges and constant change. He witnessed great changes within his family, country, and the Church as well as profound changes in theology. Calvin’s commitment to a life of pietas (piety), however, showed little fundamental change from his conversion until his death in 1564. This commitment deepened as the Lord led the reformer to trust Him more through the peaks and valleys of his life, shaping both his personal devotion and his pastoral ministry.

A life of pietas formed the foundation and the expression of what Calvin called people to be and to do as disciples of Christ. At the core of Calvin’s life and ministry was the knowledge of God, the Creator and Redeemer, revealed in Scripture and enlivened by the Holy Spirit. Such a revelation and regeneration bring about a right knowledge of both God and self. Thus, generally and mysteriously, begins the life of pietas, whereby the elect in Christ seek to live in conformity to the truth.

But what did Calvin mean more specifically by this word pietas to capture the essence of biblical Christianity and its importance to his life and ministry? To answer these questions, scholars must approach any study of Calvin from the historical, theological, and grammatical context in which he lived and labored. From a historical-grammatical perspective, Ford Lewis Battles has argued that the French theologian, while heavily influenced by his classical studies,  approached the word pietas within its horizontal dimensions of familial relationship, and, then, re-cast the view vertically with God as the focus of pietas instead of human families.[1] For Calvin, the human life is one of theology in motion lived out coram deo, before the face of God. What a person truly believes about God and life ultimately finds expression as it is lived out in a person’s life. Through a comprehensive study of Calvin’s usage of the word pietas, Joel Beeke captures the magnitude of the experiential theology it expresses. Beeke states that Calvin’s pietas is “true knowledge of God; heart-felt worship of God; saving faith in God; filial fear of God; prayerful submission to God; and reverential love for God.”[2]

approached the word pietas within its horizontal dimensions of familial relationship, and, then, re-cast the view vertically with God as the focus of pietas instead of human families.[1] For Calvin, the human life is one of theology in motion lived out coram deo, before the face of God. What a person truly believes about God and life ultimately finds expression as it is lived out in a person’s life. Through a comprehensive study of Calvin’s usage of the word pietas, Joel Beeke captures the magnitude of the experiential theology it expresses. Beeke states that Calvin’s pietas is “true knowledge of God; heart-felt worship of God; saving faith in God; filial fear of God; prayerful submission to God; and reverential love for God.”[2]

Calvin desired brevity and clarity for his individual writings.[3] Ironically, however, in his vast literary corpus, the Reformer employs the word pietas persistently. At times, this impedes clarity for his readers, unless they are familiar with the subtlety of nuance with which he deploys the word.[4] Sometimes it appears Calvin employs the word pietas dogmatically within a tightly woven theological argument dealing with the truths of Christianity from the perspective of union with Christ and forensic justification. At such times, we see a man highly influenced by the established and entrenched citadel of scholasticism that had dominated European culture for 500 years, from which many sought to break free.

At other times, Calvin’s prose is peppered with the word pietas to describe the experience or action of faithful Christian living throughout a life of obedience. This use accentuates the refinement and thoughtfulness of the rising humanistic movement.[5] The latter usage appears to incorporate the language of sanctification as part of the Christian pilgrimage, while the former usage appears to deal with precisely defined doctrinal disputes employed within the polemics of sixteenth-century scholarship. As Calvin sought to live a life of piety, he labored with specific commitments and tools to preach and teach the whole council of God. He did this work from a pastor’s heart-desire to address the entirety of the church, which embodies a great diversity of people.

With his unwavering commitment to sola Scriptura and a resolute confinement to a lectio continua exegetical hermeneutic, Calvin’s works surpass generational confinement in their application of the transcendent teaching of Scripture.[6] The seminal threads of Calvin’s conception of pietas, with its complexity of nuance and usage, permeate all his works.[7] Because Calvin’s writings on Scripture are vast and consistently deploy the word pietas while unpacking the meaning and applying it to the Christian life, studying his work with this in mind can shed light on his philosophy of ministry and personal devotion to Christ. This thread provides his readers with an important key to unlock the Frenchman’s holistic approach to “life as theology lived out” that also informs his work on any aspect of special revelation in an extremely profitable way. As Calvin labored to exegete the Scriptures in order to apply the truth to his heart as well as the hearts of those under his care, he did so with both the mind and heart in view.

[1] See the introductory essay by Battles in, Jean Calvin and Ford Lewis Battles, The Piety of John Calvin: An Anthology Illustrative of the Spirituality of the Reformer (Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1978).

[2] Beeke, “John Calvin on Comprehensive Piety,” in The Skogheim Evangelical & Reformed Conference.

[3] For a study focused upon Calvin’s hermeneutical and expositional commitments see, Richard C. Gamble, “Brevitas et Facilitas: Toward an Understanding of Calvin’s Hermeneutic,” in Calvin and Hermeneutics, ed. Richard C. Gamble (New York: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1992).

[4] Calvin “thought that the chief excellency of an expounder consists in lucid brevity.” See, John Calvin, Commentaries On The Epistle Of Paul The Apostle To The Romans, trans., John Owen, XXII vols., Calvin’s Commentaries, vol. XIX (Grand Rapids: Baker; reprint, 2003), xxiii.

[5] The term “Christian Humanist” must but be distinguished from “Italian Humanist” in order to properly understand the historical developments taking place in Northern Europe during the time period leading up to the Reformation. Hughes Oliphant Old has written extensively on the subject. He writes, “At the beginning of the sixteenth century Christian humanism meant very specifically an emphasis on the study of the humanities, that is, the literature of antiquity, biblical Hebrew, the Greek and Roman classics, the Scriptures and the writings of the Fathers in the original languages. One should not confuse Christian humanism with philosophical humanism, a philosophy which puts man rather than God at the center of existence.” See volume IV, 85-86 of, Old, The Reading and Preaching of the Scriptures in the Worship of the Christian Church.

[6] See Gamble, Brevitas et Facilitas: Toward an Understanding of Calvin’s Hermeneutic, 37.

[7] See the title page to Calvin’s first edition of his Institutes 1536, Jean Calvin and Ford Lewis Battles, Institution of the Christian religion : embracing almost the whole sum of piety, & whatever is necessary to know the doctrine of salvation : a work most worthy to be read by all persons zealous for piety, and recently published : preface to the most Christian king of France, whereas this book is offered to him as a confession of faith (Atlanta: John Knox Press, 1975).