Of the Father’s Love Begotten

Orthodox Christology in an Ancient Hymn

The beautiful hymn of the Incarnation, called “Of the Father’s Love Begotten” is set to a tune likely based on an old Gregorian chant. The lyrics of the text come to us from a man named Aurelius Clemens Prudentius (348-c.413). With a name like that, Prudentius did not write this text in English, but in Latin.

The text was translated for us by a man named John Mason Neale. If you have never heard of John Mason Neale, you might nevertheless be familiar with some of the works he has given us. Neale was an Anglican priest in the mid-nineteenth century and a hymn writer and translator. He ably translated many old Latin texts into English and set them to preexisting tunes for congregational singing in the church. Some of the hymn translations he has given us include: “O Come, O Come, Emmanuel,” “All Glory, Laud, and Honor,” and the carol “Good King Wenceslas.”

Historical Background

All that being said, Neale translated the lyrics under consideration today from the Latin, from Prudentius. Who was Prudentius? Admittedly, we do not know much about him, but he lived during the later era of the Roman Empire in what is now modern-day Spain. He was a lawyer of some sort by training, practicing law and being actively involved in public life as a provincial Roman governor in his home region of northern Spain. He was a Christian, and he collected many Christian poems and other writings. Prudentius wrote a few poems of his own, and he set many of them to music, though much of the music has been lost to us.

What’s interesting about “Of the Father’s Love Begotten” is that many people assume that it is a medieval hymn, perhaps of fourteenth or fifteenth century vintage. However, it dates back far earlier than all that. Why would we be inclined to think that it is a medieval hymn? Probably because of the tune—the Gregorian chant-like tune. And that is certainly fair, seeing that the tune does come to us out of the Middle Ages; but more on that in a moment.

There may be some cases of scrupulous theologically minded Reformed brothers who experience a bit of heartburn when we sing songs sourced from the Middle Ages because unsound doctrine was all the rage in the medieval church prior to the recovery of a strong doctrine of Scripture and salvation in the Reformation-era. For example, many, many of the hymn texts from the medieval era are hymns of praise, not to God or Christ, but to Mary. Over the years, some editors have adapted such lyrics to reorient the praises on their proper object (i.e., God) to make them more acceptable for singing by us, but the association lingers and understandably makes folks uncomfortable. Whatever troubles sometimes attend medieval hymnody, there is no problem with the more ancient hymn, “Of the Father’s Love Begotten.”

The text before us comes from sometime in the late fourth century. In fact, Prudentius lived in the midst of one of the church’s greatest theological controversies – the Arian controversy. The priest Arius denied the fill deity of Christ. In fact, Arias set his bad theology to catchy tunes that he would go around singing in order to popularize his controversial views. His theological program became so popular and widespread that we have well-attested historical accounts of street fights – yes, full-blown street fights in the marketplaces of Europe – when neighbors would get into arguments over this doctrine, the doctrine of Christ.

Arius’s most popular little ditty was, “There was a time when He was not” (referring to Christ the Son of God). There was a time when he was not; in other words, when He did not exist. According to Arius, the Son was of a similar substance, but not at all the same substance as God the Father. To use the Greek theological vocabulary of the day, Arius denied the homoousious and put forward homoiousious as the one-and-only word fit to be used to describe how the substance (as essential being) of the Son compares to the substance of the Father. In Arius’s thinking, Christ the Son of God was the greatest of all creatures, the most supreme thing that God had ever created, but he was not fully God or fully co-equal with God. To the heretic, Christ was not co-eternal with the Father; he was not right there with the Father forever; he is not fully divine. The biblical and orthodox understanding of the Incarnation, the doctrine of a fully divine, fully eternal nature wrapped up in the embryotic cells of a mortal fetus: Arius did not believe that. The long and short of it is that Arius did not believe that Christ Jesus the Son of God is eternal in the same way that the Father is eternal.

Our hymnist Prudentius lived during the heyday of Arius’ popularity, and he was having none of that heretical nonsense. There is no vague mysticism in the lyrics before us – he makes very clear and compelling assertions about the Deity of Christ Jesus, the Jesus who is God, and who came down from heaven to be our Savior.

In fact, the hymn’s only real mysticism is a proper one about the overall subject, which is indeed as profound and mysterious a subject as ever there was – the eternal begetting of God the Son by God the Father. And what does that mean? Well, who can answer that satisfactorily? Theologians have tried to do so for centuries, but the vast and delightful mystery escapes us. What does it mean that the Father and the Son and the Spirit are ever dwelling with and within one another, and that the Father, begets the Son, and the Son is eternally begotten of his Father before all worlds, and the Holy Spirit ever-processing from the Father and the Son? What mere mortal can adequately explain or fully comprehend this divine mystery of mysteries? It is the mystery of the Trinity, and we cannot comprehend or wrap our minds around it. All that is left for us to do is fall down and worship. And that is Prudentius’ approach to the subject matter here.

His hymn does its best to clarify this idea so often thought of as beyond our purview. A.S. Walpole, in his book Early Latin Hymns, says that Prudentius’ idea is that “at every hour of the day should a believer be mindful of Christ who is the Alpha and Omega, the beginning and the end. Prudentius therefore praises Him as the creator of all things, as the everlasting Son of the Father’s love begotten.”

The first three stanzas of the hymn, as you read over them, you can see how they revel in the glory of who Christ is and what he has done. In the third and fourth stanzas a call is issued successively to the whole of creation, and then the angels, and then every person on earth to praise the Lord forevermore. In the fifth stanza, we ourselves, the singers of the hymn, lift our voices in doxology. That fifth stanza was not original to Prudentius but was added sometime later by a man named Sir Henry Baker. He added it in the 1850s after Neale had translated Prudentius’ material into English, and it adds a very fitting, appropriate, and beautiful conclusion to the hymn.

Lyrics & Theology

The first stanza describes Christ as begotten of God’s love before the worlds, which, technically speaking, the heretical Arians could affirm in unison with orthodox believers. But Prudentius knew better than to let this line stand alone. Christ is not only begotten before the worlds began, He is much older still. He is the Alpha and the Source of the things that have been. He is Creation’s Lord (as it says in stanza 3). He is God (stanza 4). He is the one whose name begins the Trinitarian blessing, that doxology of stanza 5.

The first stanza proclaims that Christ is “Of the Father’s love begotten ere the worlds began to be, He is Alpha and Omega, He the Source, the Ending he, of the things that are, that have been, and that future years shall see, evermore and evermore!” This is a bold theological assertion that flatly contradicts the Arian claims that “there was a time when the Word was not.”

And notice how Prudentius moves so elegantly from affirming the Son’s full deity in stanza 1 – eternally begotten of the Father – to stanza 2 where he introduces Jesus of Nazareth, born of the Virgin Mary. Here he affirms Jesus’ full humanity. But the Son of God and Jesus of Nazareth are the same in every way, so stanza 3 makes it abundantly clear: the divine One of the first stanza, the human man of stanza two: this is the One who is the appropriate object of our Worship.

Prudentius tracks properly Christian worship beginning with the ancient prophets and leading right up to the cradle of Bethlehem – now he Shines! The Long Expected! Or are these words actually a reference to Resurrected Glory? Is that a reference to His Return and His Second Coming? Why not both? This is poetry, after all. I like to think that there’s a reverent ambiguity that Prudentius included for those who would reflect upon and sing these profound lyrics. Many writers, when referencing the first or second advent, bring them together in a kind of moment of combined adoration. We are not to distinguish too sharply, for Christ is the same yesterday, today, and forever.

That lovely refrain there in the original Latin is saeculorum saeculis (which is often translated as “ages upon ages” or “forever and ever”) was added later than Prudentius’ lifetime, probably in the eleventh century. But whoever made the addition will catch no flak from us. It makes a lovely, singable conclusion to each line. Neale chose to translate that line as “evermore and evermore.”

The second stanza acknowledges Christ as the fulfillment of Isaiah’s prophecy of the Virgin Birth and affirms the truth of the Apostles’ Creed in what we confess together about Christ, “conceived by the Holy Ghost, born of the Virgin Mary.” Surely as we contemplate that miracle, we too ought to be moved to willing praise. True Christians have always believed that doctrine – even in the face of hateful scorn from the world around us – and Prudentius had people singing about it way back in the fourth century.

The third stanza continues the theme of Christ as the fulfillment of divinely given prophecy. It calls out for the whole of creation to adore him because “now He shines, the long-expected: let creation praise its Lord!” It is a call to worship – Creation, praise the Lord who made you! – and it provides a natural segue into the fourth stanza, which is an expansion of that call to worship: “O ye heights of heaven, adore Him; angel hosts, his praises sing; all dominions, bow before him and extol our God and King; let no tongue on earth be silent, ev’ry voice in concert ring, evermore and evermore!” It summons the created heavens, the angels, all lands and kingdoms, to praise their rightful King and Creator, Christ Jesus.

And then, as I said, the fifth and final stanza in our hymnal was appended by Henry Baker and supplies suitable words of response for our hearts to sing of the glory of our Savior.

Now notice, with any good sung hymn or psalm, we are rendering praise to God (vertically) but we are also singing to one another (horizontally) as we edify one another with doctrinal truths and exhort one another with calls to praise. That is reflected in these lyrics: it is addressed to angels – you praise Christ! – it is addressed to people in all lands and kingdoms, including ourselves – you adore Him! – but then it concludes in that fifth stanza by praising the Triune God directly.

Here’s what one hymn commentator has said:

In light of this truth – that Jesus of Nazareth is Christ our God – we ask all creation to worship him. The hymn is as logically tight as it can be, given its subject. Christ is begotten of God’s love, but exists before all things. He nevertheless takes human form through the womb of the Virgin, and in doing so reveals to us the very love of God through which he was begotten. He has been the object of praise “of old,” was praised throughout recorded history, and is now to be the object of praise for all creation along with the other two members of the Godhead.[1]

It is interesting to me how orthodox this hymn is, and yet it has retained appearance in so many theologically Liberal church hymnals. It is just an irony. They do not usually tweak or edit the words, even though many of these more Liberal denominations would go so far as to deny the Virgin Birth and some of the other doctrines this hymn affirms. And yet, they let a beautiful hymn like this one remain, putting these doctrines out there plainly and letting people sing these truths with their lips.

John Mason Neale did a fantastic job when he translated Prudentius’ lyrics and brought them into English. Neale was at once a translator and a poet himself! Notice even the word order in the opening stanza – where it says “He is Alpha and Omega, He the Source, the Ending He.” Of course the word order creates the rhyme against the word “be” that just came a moment earlier, but it also creates a lovely palindrome, where “He” both begins and ends the line. He is Alpha and Omega (He brought all things into being; He is the source of all, the creator of All), but also The Ending He. It ends with He, there. Christ is the end all things, the telos, the great point upon which all time and history and the universe terminates; everything finds its meaning in Him, and all things are pointing and leading to Him. I love how He, Christ, brackets that whole line. That is a fitting and poignant poetic touch.

Notice also how the alliterative “b” sounds tie together the first and second stanzas,

(1) Of the Father’s love begotten ere the worlds began to be,

He is Alpha and Omega, He the Source, the Ending He,

of the things that are, that have been…

(2) Oh, that birth forever blessed, when the Virgin, full of grace,

by the Holy Ghost conceiving, bore the Savior of our race;

and the babe…

Even a subtle literary device such as alliteration, creates a lovely unity between the first stanza on Christ’s eternal nature and the second stanza which focuses on His perfect humanity, His incarnation.

The Tune

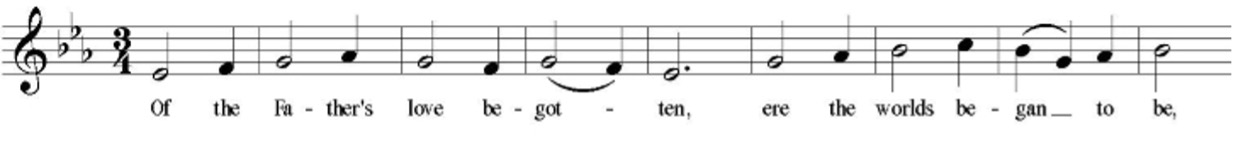

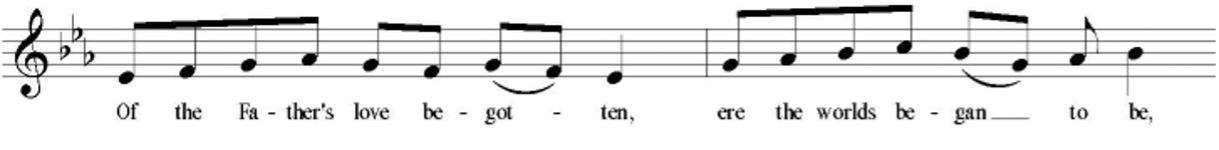

The tune DIVINUM MYSTERIUM is originally a plainsong chant from the twelfth century. It was originally more simple, as were many chants, and it grew over time into this harmonized, ornamented, and sweeping chant tune.

The sweeping chanting quality is apparent from the similarity of its seven phrases, all of which involve arch shapes. But each arch is different, and the differences relate well to the relative placement of the text in each stanza. Notice how deliberately the words match the ascending nature of the notes at the ideal point in each line: the highest arch of the tune itself brings us to a climax of music corresponding to a climax of doctrine depending on the line:

He is “Alpha and Omega”; by “Holy Ghost conceiving” and “hymn and chant and high thanksgiving.”

The earliest printed form of the tune (1582) gives us a simpler version of this tune: almost a kind of gigue or dance rhythm:

Some modern hymnals even use this rhythm, which sounds more like that of a Reformation hymn-tune. I personally prefer and recommend the rhythm of these nice, even eighth-notes found in the Trinity Hymnal.

One hymn commentator puts it like this, quite well:

In this hymn, as in “Let All Mortal Flesh Keep Silence” and “Oh, Come, Oh, Come, Emmanuel,” the subtle freedom of a chant-like yet accessible rhythm focuses attention on the words, even as a sobering contrast to the jauntier rhythms of other hymns; it communicates awe and reverence appropriate for the mystery of the eternal begetting of Christ by God the Father.[2]

—

[1] Joshua Drake and Paul Munson, “Of the Father’s Love Begotten,” CongSing.org, http://www.congsing.org/of_the_fathers_love.html.

[2] Ibid.