In 1857, shortly after he was installed as the new pastor of the Roxburgh Free Church on Hill Square adjacent to the Royal College of Surgeons in Edinburgh, Walter Chalmers Smith (1824-1908), began to compose congregational hymns to complement his sermons. He was inspired by the example of the unrivaled father of English hymnody, Isaac Watts, who wrote more than a thousand hymns and psalm settings, often to accompany his sermons at the Mark Lane Chapel across from Tower Hill in London. Ten years later Smith would publish what he would call “the choicest of my labors” in Hymns of Christ and the Christian Life.

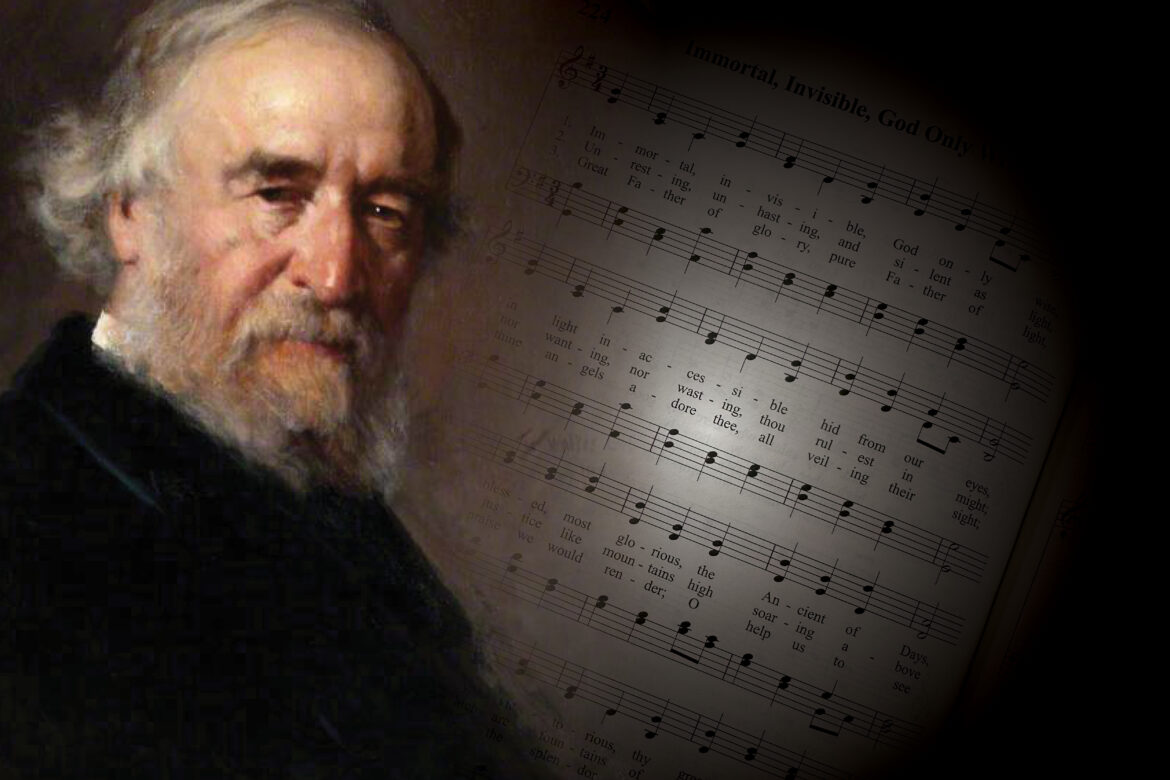

The collection included the hymns, “Earth Was Waiting, Spent and Restless,” “Lord, God, Omnipotent,” “Our Portion Is Not Here,” “There Is No Wrath to Be Appeased,” “Faint and Weary, Jesus Stood,” and the classic for which he is best known today, “Immortal, Invisible, God Only Wise.”

Smith was born in Aberdeen, the son of Walter and Barbara Smith, and named for both his father and the great Scottish Reformer Thomas Chalmers. His father was a master cabinetmaker and a Reform-minded deacon in the Church of Scotland, so his son was faithfully raised in the lively days of evangelical resurgence during the Ten Years Conflict and the Disruption.

He was educated at the Aberdeen grammar school and at the University of Aberdeen’s Marischal College. After graduation in1841 he began to study for a legal profession but two years later – during the tumult of the Disruption – his faith was stirred to ardency by the example of Dr. Chalmers. He sensed a call to gospel ministry and determined to enter the newly established Free Church’s theological seminary, New College, Edinburgh.

On Christmas morning 1850 he was ordained as the pastor of the Chadwell Street Scottish Free Church in Islington, London, a neighborhood then undergoing dramatic renewal with the construction of the nearby King’s Cross railway station. In 1853 he was called back to Scotland to serve at Milnathort in the parish of Orwell, Kinross-shire. In 1862 he was chosen to succeed Robert Buchanan, who with Dr. Chalmers had been one of the leaders of the Disruption, as pastor at the Free Tron Church, Glasgow. In 1876 he was called to the Free High Kirk, which worshipped in the beautiful New College building designed by William Playfair on the Edinburgh Castle Mound site of the old palace of Princess Regent Mary of Guise. The capstone of his ministry came in 1893 when he was chosen to serve as Moderator of the General Assembly for the Free Church of Scotland.

But it was during the years of his pastorate at the Roxburgh Free Church, between 1857 and 1862, that Smith began his prolific career as a poet, hymn writer, and novelist. Ideas for his creative writing most often came to him as he studied for his Lord’s Day sermons. But the inspiration for “Immortal, Invisible, God Only Wise” surprisingly came during a dinner with eleven other New College alumni as they reminisced together about the halcyon days immediately following the Disruption when they sat under the impassioned teaching of Dr. Chalmers.

Biographer James Cothran said of Thomas Chalmers, “He was of the rare order of men whose students are their children; who draw to themselves that young love which is above the love of women and by some magnetic power, bring the youths flocking to them from afar, from the very ends of the earth. He himself always young, had the Socratic love about him, the divine love for the immature, identifying them with truth and progress, which elicited their fondest regard in return. Modern universities scarcely afford a parallel; one must go back to the attractions of an Abelard or an Erasmus.”

Indeed, W.M. Taylor observed, “To the end of his days he had around him a circle of loving and devoted students, all of whom were fired with enthusiasm which they had caught from his lips. He was not so much an instructor as a quickener. The other professors laid the materials in the minds of the students, but he brought and struck the match, which kindled these materials into a flame that burned with an energy kindred to his own.”

As the men gathered around the dinner table recalled their happy bygone student days, they particularly recollected the lofty phrasings of their mentor’s prayers. They rehearsed his most striking and memorable catchphrases — many of which now shaped cadences of their own prayer vocabulary. Realizing the riches that their conversation had uncovered, Walter Chalmers Smith began to scribble down their remembrances on a scrap of paper he retrieved from his frock coat. A few days later he transcribed the notes into his commonplace journal, realizing he had the puzzle-piece makings for lyrics that would beautifully balance in adoration of the Lord both the intimate and ineffable.

The final composition, gleaned from the language of 1 Timothy 1:17 and Psalm 147 as well as from the extempore prayers of Dr. Thomas Chalmers, acknowledges human finiteness in the face of the One hidden by the “splendor of light,” who “rulest in might,” but who is nevertheless our “Great Father of glory, pure Father of light.” It regaled both the immanence and the transcendence of our Sovereign God.

I have always loved this hymn. But knowing the story behind it, I now love it all the more.