The following post is part of our ‘Principles of Reformation’ series. For the first post in the series, please click here.

The terms reformation and reform have different meanings for different people. Historians use the term the Reformation to define the momentous events of the sixteenth century that shattered the Roman Catholic hegemony in Europe and established Protestantism in its place. For many, therefore, reformation seems to mean doing things just the way the Reformers did. In the realm of theology, these terms identify a particular school of thought. Reformed or, more broadly Reformation theology describes a system for understanding the Bible and for organizing faith and life. This system is highlighted by the “solas” or “alones” of the Reformation: sola scriptura (Scripture alone), sola fide (faith alone), sola gratia (grace alone), solus Christus (Christ alone), and solid deo gloria (glory to God alone).

In what follows, I seek to show that reformation is a biblical concept, indeed an essential biblical mandate for every era of the Christian church. Reformation was a major concern to the prophets and apostles, and in the flow of redemptive history we see a definite biblical pattern of reformation. It is this biblical pattern and principle of reformation that we must understand, making observations and drawing lessons for our own challenges in the church today.

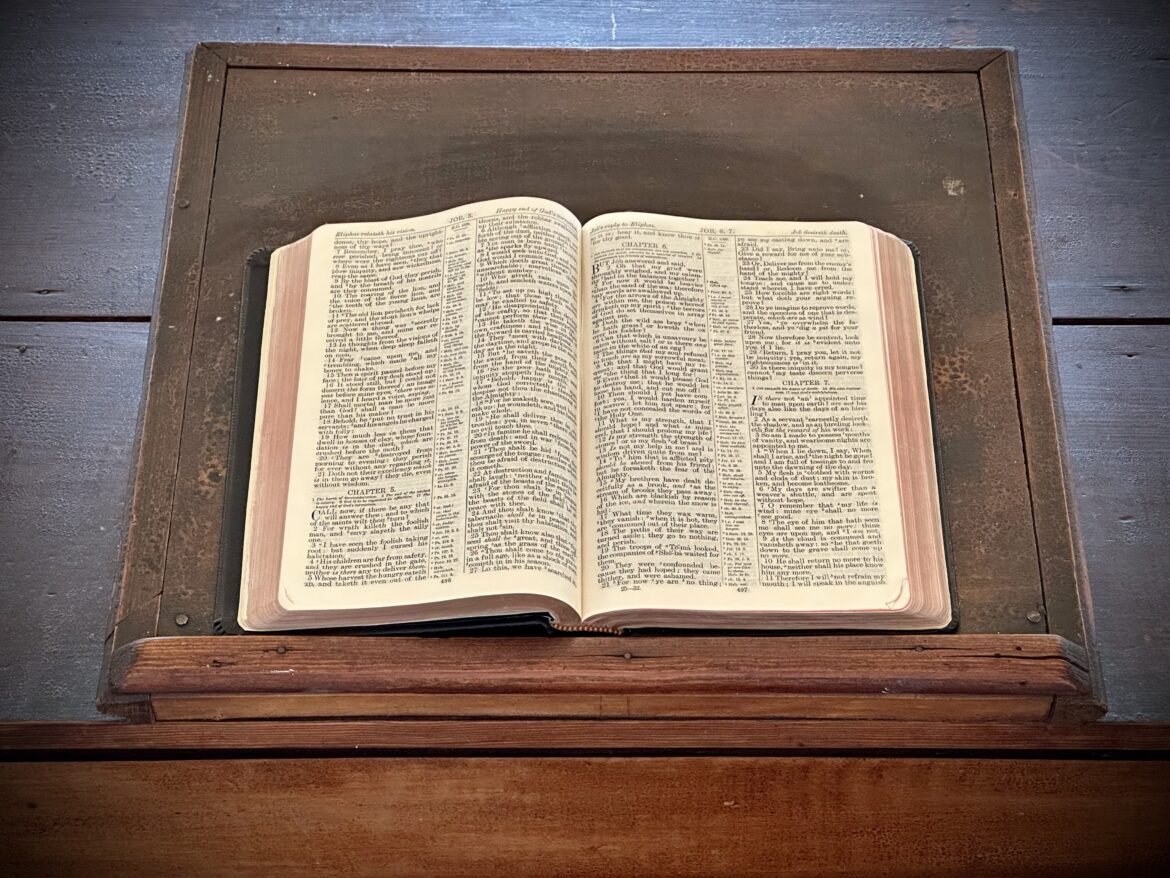

God’s Word Lays the Sure Foundation

The fundamental principle of the Reformation is God’s inspired and inerrant Word inscripturated as His authoritative self-revelation in the Bible, which is wholly sufficient for faith and practice. The Protestant scholars and theologians of the generation following the more famous magisterial Reformers recognized that God’s Word is the fundamental principle of knowing God[1] and being reformed after His holy character expressed in His revealed will.

Every principle of reformation which will be examined in this blog series comes from the Bible. Because the Scriptures themselves employ a clear pattern of fidelity versus infidelity, reformation versus deformation, then all Christians may look to these principles as a clear guide for thought and action. This is very much what we need today – not partisan pressure tactics or debates regarding mere style and preferences, but rather an analysis and framework for discussion that is demonstrably biblical and applicable to our own time. Indeed, the Reformers themselves stressed this imperative, a re-forming according to the sacred and authoritative Scriptures.

What is the consequence of failing to recognize that God’s Word is the fundamental principle of reformation? Deformation. There is a definite pattern of deformation that occurs all through the history of God’s people in Scripture. There is a pattern of disobedience and folly that is well documented in the Scriptures. Just as reformation involves a discernible pattern and flow, so also does deformation with all its terrible results.

Is Reformation a Biblical Idea?

As we lay a foundation for the reformation principles that follow, we must ask ourselves, “Is reformation itself a biblical idea?” If we are to submit ourselves unreservedly to Scripture in examining the idea of reformation, we must first identify the biblical support for the idea of reformation. We are concerned that we derive our thoughts from the language of the Bible, that we be constrained by the actual scriptural usage, and yet we quickly discover that the term reformation does not often appear in the Bible. Does this not prove that we are merely inserting our own rigid view into the interpretation of Scripture?

If you look up the noun reformation in your concordance, you will not be impressed by the results. In the New International Version (NIV), the word does not occur at all; in the King James Version (KJV) it occurs just once; and in the New American Standard Bible (NASB) it also is found only one time (Heb. 9:10). If you use a computerized version and you type in the verb reform, you will find only slightly better results. The NIV uses the word four times, all in Jeremiah and always in the form of a command. We find reform only once in the NASB and not at all in the KJV. By this standard reformation must not really be a biblical concept, or not an important one anyway. The prospects for discerning a biblical pattern seem dim at this point.

There are, however, two other words that describe what reformation is all about, and they are repeatedly encountered in the Scripture. These words are remember and repent. That is what reformation is – remembering God and His saving work and His authoritative Word, repenting from unfaithfulness in heart and in action and to the pattern God established through His Word when He formed a people for Himself. It is in the use of terms such as these that reformation occurs all through the Bible, defining faithfulness in every generation.

One of the great reformation texts is found in the opening chapters of the book of Revelation, the letters to the seven churches from the Lord Jesus Christ. In these chapters we see our Lord, risen and exalted, standing amidst the lampstands of the church and holding the seven stars of the churches in His mighty right hand. Jesus, in this last book of God’s Word, appears as the Great Reformer of His own church. That is what the seven letters He gave to John address – the reformation of what Christ Himself purchased and then formed through His servants the apostles. Ephesus was the mother church of these seven, and in the first of the letters Jesus praises this important congregation:

I know your works, your toil and your patient endurance, and how you cannot bear with those who are evil, but have tested those who call themselves apostles and are not, and found them to be false. I know you are enduring patiently and bearing up for my name’s sake, and you have not grown weary. (Rev. 2:2, 3)

The next paragraph, verses 4-6, presents a well-developed definition of reformation, establishing it firmly as a mandate from the Lord:

But I have this against you, that you have abandoned the love you had at first. Remember therefore from where you have fallen; repent, and do the works you did at first. If not, I will come to you and remove your lampstand from its place, unless you repent.

Reformation, as we see it biblically defined and commanded by the risen and exalted Lord Jesus Himself, consists of both holding fast to what we have received from God and the ongoing work of repenting and conforming to His Word in every area and aspect of our lives.

The Biblical Pattern of Reformation

This reformation pattern of remembering, repenting, and conforming to God’s Word is not only in a few select scriptural texts, but is present in the very fabric of the biblical revelation. There is a biblical pattern that not only commends but demands reformation.

The pattern is this: First, there is formation by God through the work of His prophets and apostles and in response to His mighty saving acts in history to gather a people for Himself. What follows, however, is sin and unfaithfulness. This is deformation, which is an abandonment of those commands and principles established by God in the forming of His people. Finally, in response to the presence of deformation, the Bible demands reformation. Formation-deformation-reformation. This is the pattern amply described and founded in Scripture, corresponding perfectly to the reality of our lived experience in and as the church.

I have pointed out that the term reform is seldom found in the text of Scripture, although its constituent parts of remember and repent are commonly found. It is worth pointing out, however, that when the word reform does occurs, as in Jeremiah 35:15 (NIV), it is used as a summary description for the whole work of all the prophets. Again and again I sent all my servants the prophets to you. They said, “Each of you must turn from your wicked ways and reform your actions; do not follow other gods to serve them. Then you will live in the land I have given to you and your fathers (emphasis mine). This is what is going on in the books describing Israel’s life from the time of Moses to God’s judgment in the destruction of the city and its temple. Israel’s rejection of the prophetic call to reformation – to remember and repent – anticipated God’s judgment on the deformed nation, a judgment that came to a head in the Babylonian conquest and captivity.

Even after this terrible judgment, reformation is what we see going on in the pages of the Old Testament. God’s deliverance of Israel in the time of Ezra and Nehemiah was a classic example of reformation. It was a reformation performed by God through His servants, with a fresh application of the principles and commands seen in the original formation under Moses.

Biblical Reformation for Today

As we reflect on this biblical pattern of formation-deformation-reformation which evidences itself in the macrostructure of redemptive history as well as in particular events and prophecies of both Old and New Testaments, there are two errors into which we may fall. On the one hand many discount talk of trouble and the need for reform as alarmist and unduly negative. On the other hand, others withdraw in despair over the singularly wretched conditions of our day.

But what we are going through today, as so many churches are wandering from biblical principles – both in terms of the means they employ and the ends they are seeking – is not something strange or unique. This is a vital biblical truth for us to understand. On the contrary, it is the normal experience of the church. Scripture shows us that deformation is not something strange or unusual, but is a recurring phenomenon we should expect, watch out for, and respond to with awareness and resolve, but not with surprise or dismay.

The apostle Peter wrote in his first epistle, “Beloved, do not be surprised at the fiery trial when it comes upon you to test you, as though something strange were happening to you” (4:12). We might adopt that language and say, “Beloved, do not be surprised at the woeful state of the church and the urgent need for reformation, as though something strange were happening.” One way or another, every generation encounters deviation from the pattern set down in Scripture, and every generation has to combat deformation with biblical reformation.

In generation after generation, as you go back you find the same thing. There is therefore a constant need for and a tradition of reformation that stretches back to the great Reformers, and back before them to the early church and the apostolic age itself. The point is this: Let us not be discouraged or alarmed by the great need for reformation in our day, but rather let us show the kind of bold resolve of those “sons of Issachar” described in 1 Chronicles 12:32 as “men who had understanding of the times, to know what Israel ought to do.”

To achieve this we first of all must understand the fundamental principle of reformation, the Bible, where reformation is set forth as a constant need and a serious challenge of faith. But it is also a privilege for those who wish to serve our Lord Jesus Christ in the age in which we are found, and it comes with great promises that should make us confident of God’s blessing, particularly as we put our trust in His mighty, saving Word.

This material was adapted from the introduction to Turning Back the Darkness: The Biblical Pattern of Reformation (Wheaton, IL: Crossway Books, 2002). It is republished here with permission of the author.

[1] The Latin term they would use most frequently for this is principium cognoscendi theologiae, the principle or foundation of knowing theology.